Writing reports accounts for quite a lot of my working time. There are condition reports, treatment recommendations, loan reports, treatment reports. I’m never far from my notebook when I’m working.

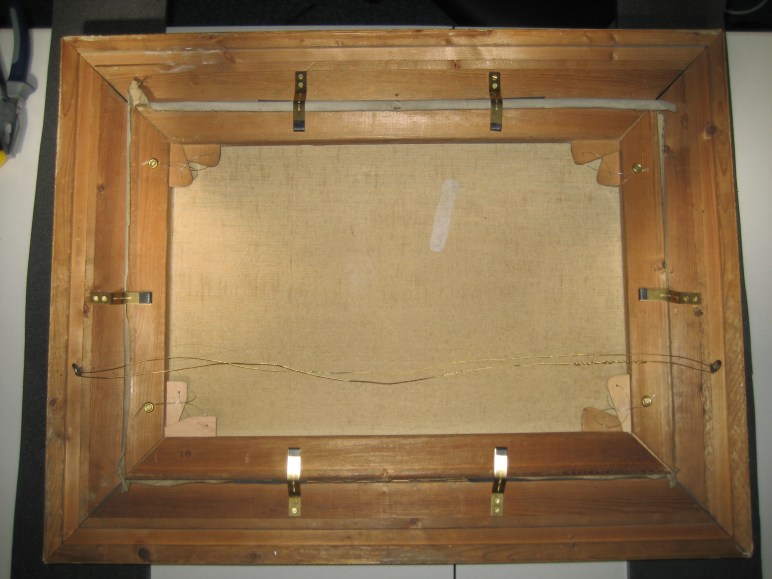

These reports aren’t just box-ticking (although sometimes box-ticking is exactly what’s involved) but are important records of the works at a particular time. Sometimes it’s obvious what purpose a report will serve. When a work goes out on loan for an exhibition, whether that’s between galleries or to a gallery from a private collection, we need to make a note of its condition before it travels and see how it looks when it gets there.

Other reports I write are often for the interest or information of some unknown person at an unspecified time in the future. Sometimes it can feel a bit futile, as if nobody will be interested, but actually I’m always grateful to see a previous report for a painting I’m looking at. It’s reassuring when you find that nothing much has changed, or it can narrow down a time period during which a change has occurred; it can save you time if the previous conservator has recorded something that will influence your treatment proposal.

Something I hadn’t previously considered is that there is the possibility that something I record could be more significant than I understand at the time. Recently in the news there was a story of a painting being identified as Nazi loot thanks to the detailed condition report of a museum employee during the occupation of France who recorded the presence of a small hole in the canvas. This, along with the present day conservators who have looked carefully and recorded what they’ve found and compared it to these old reports, should lead to the painting being reunited with the family that it was stolen from. Whilst I expect that most of the reports I write will be merely of interest in the future, the potential for my observations to be of greater significance will keep me motivated as I sit down to write the next batch.